Field Diary 2019.3 © Abydos Archaeology

Fig. 1. Architectural illustrator Damon Cassiano planning a Middle Kingdom chapel in the Abydos North Cemetery. Photo by Robert Fletcher for North Abydos Expedition © 2003

How do you see into the past? Step 1: Get down in the dirt. Step 2: Document everything. Step 3. Document some more. Step 4. Document, document, document! Step 5. Repeat. (Figs. 1-3). Archaeological documentation means many different things — measuring, drawing, mapping, photographing, registering and housing material, and even publishing. It is one of the most important aspects of every stage of fieldwork, in order to ensure the long-term preservation of excavated material and all data associated with it, including not only objects, features, architecture, and landscapes, but also all of the modern people and activities associated with work and life in the field. In a word: context. Read on to see how advanced technologies like 3D modeling are adding new dimensions of context to traditional methods of archaeological documentation.

Fig. 2. Photographer Greg Maka shooting a Middle Kingdom coffin at the Shunet el-Zebib. Photo by Somer Kearny for North Abydos Expedition © 2012

Fig. 3. Archaeologist and photographer Ayman Damarany documenting the excavation of Old Kingdom tombs in the Abydos North Cemetery. Photo by Matthew Adams for North Abydos Expedition © 2018

On the Shoulders of Giants

Fig. 4. British archaeologist Flinders Petrie photographing at Abydos in 1899. Photo courtesy of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology © UCL

Excavation is at the heart of all archaeology — it is how we see into the past. But any excavation is only as good as the body of knowledge and understanding it supports through documentation, conservation, outreach, and publication. That’s because archaeology as a field science is inherently destructive. To excavate sites and objects buried in the past and learn from them in the present, we have no choice but to disturb the very context in which they are preserved. It was not until the late nineteenth century that archaeologists like Flinders Petrie began to systematically look at sites and objects in context, and to see not just the objects themselves, but also the information associated with them in situ as valuable to our study of the past (Fig. 4). At a time when archaeology’s early pioneers were looking for new ways to document the process of excavation through field notes, illustration, and artifact registration, photography became one of their most important tools. The documentation of excavated features and artifacts in situ was a key difference that separated scientific from non-scientific archaeology — it meant, for example, that the data associated with objects in context could also be preserved in the archaeological record, rather than separated and ultimately lost as objects moved from sites to museums. Photographic documentation, in particular, revolutionized archaeological fieldwork by providing the most accurate visualization of archaeological context possible.

British archaeologist Flinders Petrie is often called the “father of archaeology” for his pioneering field methods, through which he helped make the study of excavated artifacts into professional archaeology. He is a giant figure in the archaeology of Abydos, in particular, and his extensive work at the site gives it a special place in the history of archaeology everywhere. Petrie excavated a total of five seasons at Abydos between 1899-1903 and 1921-1922. His first excavations at the site were in the royal necropolis at Umm al-Qa‘ab, followed by the area surrounding the Osiris Temple at Kom al-Sultan, and finally at the First Dynasty royal enclosures in the North Cemetery. Both of the latter two areas form part of the Expedition’s current research area. As the first major site where Petrie worked continuously over several years, Abydos was formative to the development of his revolutionary field methods, including the use of photography to document the process of excavation. Other archaeologists who pioneered the use of photography in archaeology, like John Garstang, also excavated at Abydos in the early twentieth century. Following in the footsteps of these early pioneers, and in many ways building directly on the technological innovations they brought into the field over a century ago, at Abydos today we are introducing a new kind of archaeological photography that extends the range, accuracy, and reach of data collection in situ.

Advancing the Frontier of Archaeological Documentation, One Thousand Photos at a Time

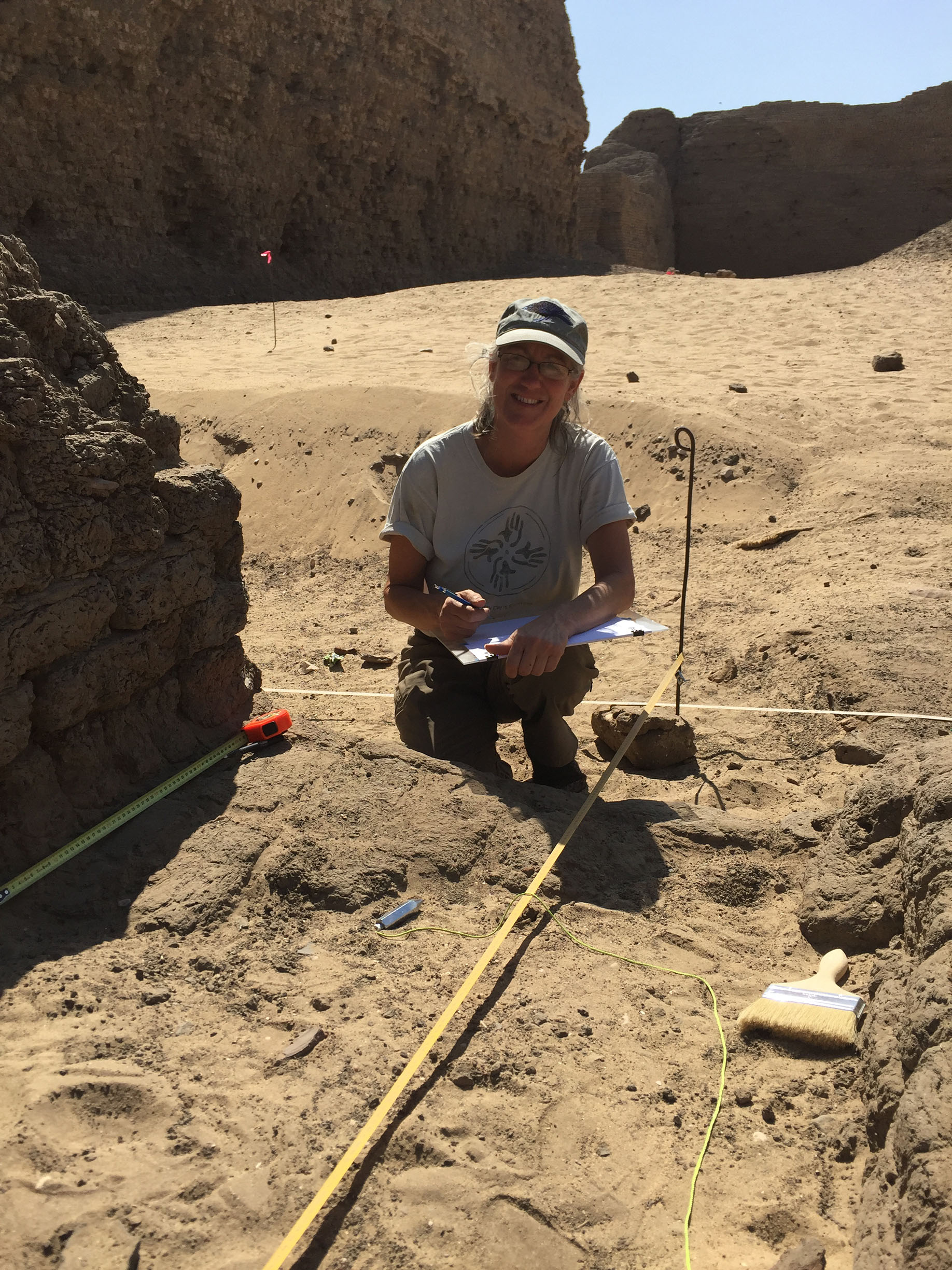

Fig. 5. Archaeologist Kay Barnett mapping the east corner gateway of the Shunet el-Zebib. Photo by Wendy Doyon for North Abydos Expedition © 2019

Traditional photography and detailed scale drawing of both sites and objects have long been essential components of archaeological documentation at Abydos. Since 2009, we have been especially fortunate to work with National Park Service archaeologist Kay Barnett, who is responsible for detailed scale mapping and architectural documentation at the Shunet el-Zebib each season; and since 2018, with Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities archaeologist Ayman Damarany, who is the Expedition photographer (Figs. 5,6). This season, we are triply fortunate to be joined by 3D specialist Blair Simmons, who brings, for the first time, a unique and innovative skillset at the intersection of art and technology to the archaeology of Abydos (Figs. 7,8). Prior to the start of the season, Blair and Expedition co-director Matthew Adams mapped out a preliminary plan for the introduction of 3D modeling in the field, which initially focused on testing the feasibility of modeling different scales, sizes, and types of objects for analytical and study purposes, as well as the possibility of modeling the architecture of the “Portal” Temple of Ramses II and the east gateway of the Shunet el-Zebib, as part of this season’s overall field program.

Fig. 6. Archaeologist Ayman Damarany photographing the east corner gateway at the Shunet el-Zebib. Photo by Kay Barnett for North Abydos Expedition © 2019

Fig. 7. 3D specialist Blair Simmons photographing the east corner gateway at the Shunet el-Zebib. Photo by Kay Barnett for North Abydos Expedition © 2019

Fig. 8. Blair and Ayman shooting objects for 3D modeling. Photo by Heather White for North Abydos Expedition © 2019

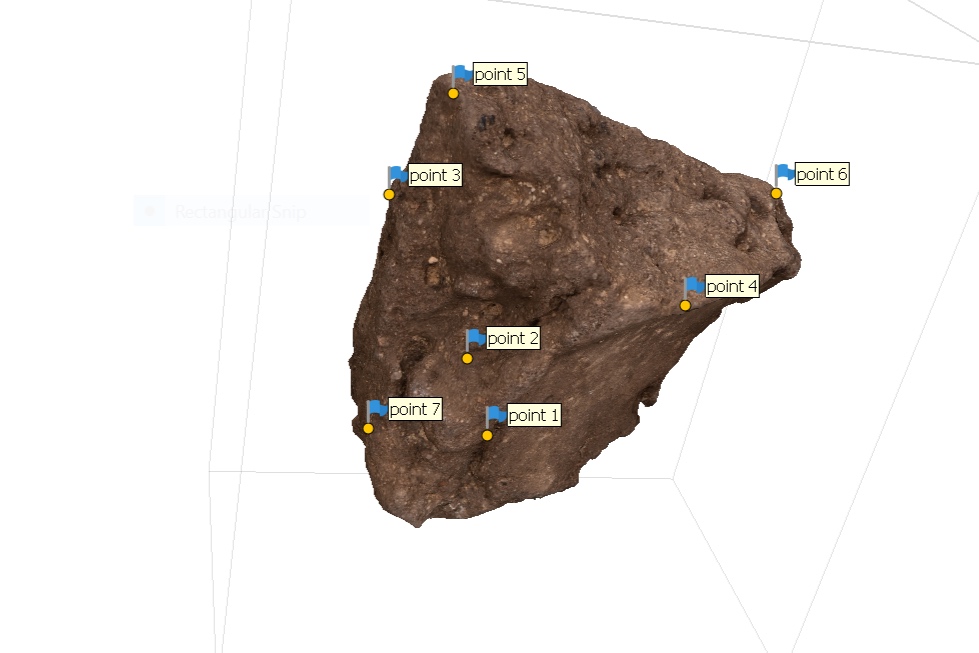

Why 3D modeling, you ask? Because, while traditional drawings and photos capture a great deal of information about the original context, existing condition, and details of excavated objects, as two-dimensional representations, they by their very nature cannot capture the full three-dimensional reality of either objects or archaeological and architectural features (Figs. 9,10). Further, because excavated objects and — obviously — architectural features cannot be taken out of Egypt for study or analysis, 3D modeling allows for remote examination in a way not previously possible, offering exciting new possibilities for both analytical and educational purposes. After considering different kinds of 3D modeling technologies, like laser scanning, Matt and Blair settled on photogrammetry as a relatively inexpensive and highly effective method of capturing data. Photogrammetry is the use of photography in surveying and mapping to measure distances between objects. It captures color information, in addition to geometry, and can be used at any scale. They chose Agisoft Metashape, a software program that performs photogrammetric processing of digital images and generates 3D spatial data for use in GIS applications, cultural heritage documentation, and visual effects production, as well as for indirect measurements of objects of various scales. Metashape is the industry standard in photogrammetry, and will allow anyone with a camera to scan and glean data on-site in the future.

Figs. 9, 10. Artist and archaeological illustrator Mária Iván brings an ancient face to life during excavations at the Abydos North Cemetery. Photos by Greg Maka for North Abydos Expedition © 2013

The idea for this season was to do a proof of concept: How would photogrammetric 3D modeling work in the field? What exactly would be involved in capturing the data to create the models? How successful would the modeling be for different kinds of material with a three-dimensional aspect, from small objects like seal impressions to larger relief fragments, stelae, offering trays, and sculptures, and even further up the scale to the architecture of ruined but complex structures? How feasible is the creation of a virtual collection of excavated material that could be made accessible via the Internet to students, scholars, and the general public anywhere in the world?

Fig. 11. Seal impression of King Khasekhemwy (c. 2650 BCE) excavated at the Shunet el-Zebib. Photo by Amanda Kirkpatrick for North Abydos Expedition © 2010

Once the season was underway in early February, 3D object scanning got off to a quick start with immediately exciting results. Objects that are traditionally very difficult to photograph and illustrate in the round — like seal impressions — are ideal subjects for modeling (Fig. 11). This is of particular significance at a site like Abydos, where seal impressions are among the most common and historically valuable inscriptions found in the excavations. To date, twenty objects from previous seasons of excavation at the Abydos North Cemetery have been scanned this season, including three Early Dynastic seal impressions (Figs. 12,13).

Fig. 12. 3D modeling of an Early Dynastic seal impression from the Abydos North Cemetery, front view in process. Photo by Blair Simmons for North Abydos Expedition © 2019

Fig. 13. 3D modeling of an Early Dynastic seal impression from the Abydos North Cemetery, back view in process. Photo by Blair Simmons for North Abydos Expedition © 2019

Fig. 14. Architectural modeling of the east corner gateway of the Shunet el-Zebib — step one, photographing. Photo by Blair Simmons for North Abydos Expedition © 2019

Architectural scanning on-site has presented more challenges than object modeling, but with equally exciting results. Returning to our long-term architectural conservation program at the Shunet el-Zebib for the first time since 2012, one of the main goals of the 2019 season is the excavation and comprehensive documentation of the east corner gateway. The idea here was to scan the architecture of the gateway for the purpose of detailed documentation and condition assessment prior to any conservation interventions (Figs. 14-18). As with the object scanning, the on-site photogrammetry uses DSLR camera technology to scan the architecture, and the shooting is done in camera RAW, which captures much more information from the lens than is visible in TIFF or JPEG files. RAW images, for example, record as many as 64 times more levels of brightness than JPEG images, in which large amounts of original image data are compressed and lost. Consequently, the amount of data captured in these hi-res 3D scans produces extremely large OBJ files. Data capture at the east gateway alone resulted in 1,000 photos, far exceeding this season’s processing power for producing a finished 3D model in the field. Given the constraints of both time and computing power, most of the objects captured and the larger architectural models will be finished post-season.

Fig. 15. Architectural modeling of the east corner gateway of the Shunet el-Zebib — step two, photo alignment. Photo by Blair Simmons for North Abydos Expedition © 2019

Fig. 16. Architectural modeling of the east corner gateway of the Shunet el-Zebib — step three, dense cloud image. Photo by Blair Simmons for North Abydos Expedition © 2019

Fig. 17. Architectural modeling of the east corner gateway of the Shunet el-Zebib — step four, 3D imaging. Photo by Blair Simmons for North Abydos Expedition © 2019

Fig. 18. Architectural modeling of the east corner gateway of the Shunet el-Zebib — step five, orthorectified image. Photo by Blair Simmons for North Abydos Expedition © 2019

The team initially thought it would be possible to also produce elevations — flattened, orthorectified photos of different wall sections suitable for annotation — directly from a 3D scan of the entire structure, but the processing requirements were again too great. At this point, Matt, Blair, Kay, and Ayman had to go to the drawing board together to find a 2D solution for the photo elevations, deciding to scan each wall elevation separately. The marriage of tried and true methods of archaeological illustration with new technologies is desirable because it adds a highly detailed and accurate layer of data to traditional forms of documentation, in this case the ability to illustrate over orthorectified photos. But adding this third dimension of context is a complex negotiation between different scientific art forms that each involves a degree of interpretation. Photogrammetry captures more information than has previously been possible, but like scaled drawing or traditional photography, it still produces a representation, not an exact replica of the subject. By retaking and reducing the number of photos per elevation, Blair was able to make extremely detailed images of each wall section for Kay to annotate. In addition, the architectural scans are properly scaled and include georeference coordinates that position them in real space and in “Abydos space” in ArcGis. Still, archaeological documentation is never an exact science — a margin of error exists in every method. Whether using photogrammetry or traditional illustration, artists make informed choices about how to interpret objects and monuments, and no matter how advanced their tools are, it is always the artists, not the tools that create the images (Figs. 19-22). Even something as simple as the thickness of pencil lead, for example, can change the nature and accuracy of a drawing. Just as the quality of archaeological illustration depends on the artist, so too does the quality of a hi-res scan — whether for 2D elevations or 3D models — depend on the photographer. In the case of the east corner gateway at the Shunet el-Zebib, when Blair’s scaled photos and Kay’s hand-drawn maps were checked against each other, they showed exactly the same measurements. Testing this dual method of documentation in the field demonstrates that, in the right people’s hands, both processes are highly accurate in measuring and scaling, and that by working together, the outcome in terms of data collection is greater than the sum of its parts.

Fig. 19. Archaeologist Kay Barnett inking a detailed scaled drawing of the Shunet el-Zebib. Photo by Gus Gusciora for North Abydos Expedition © 2012

Fig. 22. Archaeologist Ayman Damarany photographing excavations at the Abydos North Cemetery. Photo by Kay Barnett for North Abydos Expedition © 2018

Fig. 20. The tools of architectural illustration. Photo by Greg Maka for North Abydos Expedition © 2009

Fig. 21. Archaeologist Kay Barnett inking a detailed scaled drawing of the Shunet el-Zebib, detail. Photo by Gus Gusciora for North Abydos Expedition © 2012

Another challenge — and benefit — of introducing 3D modeling in the field is negotiating the constantly shifting priorities that are inherent to the process of excavation. When artifacts come to light that cannot be saved in their existing condition, they can immediately get bumped to the top of the priority list for comprehensive documentation in situ and conservation. The discovery this season of an elaborate Third Intermediate Period painted coffin at the Shunet el-Zebib afforded an unexpected, but welcome, opportunity to scan an object at risk and provide a higher level of documentation. In this case, having a 3D specialist in the field was critical to saving the object, as photogrammetry provided the documentation necessary to allow for detailed study and accurate reconstruction of the coffin in the future (Fig. 23).

Fig. 23. Scanning the painted coffin discovered this season outside the east corner gateway of the Shunet el-Zebib. Photo by Blair Simmons for North Abydos Expedition © 2019

Seeing the Past, by Looking to the Future

Fig. 24. Photographer Greg Maka standing on top of the largest photo tower ever constructed for archaeological documentation at Abydos. Photo by Somer Kearny for North Abydos Expedition © 2012

The tools introduced this season have laid the foundation for a long-term 3D modeling program at North Abydos. Despite the unavoidable challenges and ever-shifting priorities of complex fieldwork, our first attempts to scan both objects and architecture this season have been remarkably successful and we are optimistic about the integration of 3D technology into the holistic framework of archaeology at Abydos. In every component of fieldwork, from traditional methods of excavation and recording to advanced conservation practices, we are committed to investigating, documenting, and sharing knowledge about the past in the least destructive and most accessible ways possible (Fig. 24). 3D models of objects are not “real” objects; rather, they are one more form of documentation, like illustration or photography, which visualizes archaeological data for archival preservation and access, albeit one which greatly intensifies the research potential of archaeology by preserving more detail about, and allowing broader access to study material than ever before.

Excavation will always be at the heart of archaeology. But just like our predecessors at Abydos a century ago worked, within the limits of their own time and place in the history of science, to make archaeology more scientific and less destructive than it was in previous generations, we stand on their shoulders now, working to build a future of open access to as much archaeological data as we can possibly capture for the benefit of those who will continue to study the past long after we too are history.